- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

PT KONTAK PERKASA FUTURES - Akira Toriyama's original Dragon Ball manga

ran for over 500 chapters, not including spin-offs. The various anime

adaptations span over 600 episodes, not including movies and OVAs. With

those numbers in mind, it may seem modest that Dragon Ball spawned only 80 or so video games to date. Yet that's a game library few other manga or anime titans can boast.

Of course, Dragon Ball is one of those stories seemingly made for video games, whether it's the goofy adventures of a young Goku or the somewhat darker intergalactic brawls of a grown-up Goku, his family, and a limitless cosmos of hostile aliens. The Saiyan hero and his retinue are superheroes with absurd powers and comical overtones, and they fit right into video games from basic shooters to cutting-edge fighters.

But where did it all begin? If you want to be technical about it, the first Dragon Ball video game was a self-contained LCD handheld device entitled Dragon Ball: Pilaf no Gyukushu. Toy-and-game heavyweight Epoch Co. released it in August 1986 with a second game, Taiketsu Son Goku, right on its heels. Like Nintendo's Game and Watch series and other LCD gadgets of the day, these games offer simple black-and-white graphics, and playing one is akin to messing around with a violent calculator. And let's face it: those LCD trinkets don't count as real video games. Just ask any kid who ever got a Tiger Electronics handheld instead of a Game Boy for Christmas.

The first full-fledged Dragon Ball games wouldn't be far behind, though. A month after their LCD handhelds hit the market in 1986, Epoch released Dragon Ball: Dragon Daihikyou for their Super Cassette Vision. The original Cassette Vision and its Super successor were short-lived pioneers of the console market. Dwarfed by Nintendo and Sega systems, they were rarely seen outside Japan. Few were the Europeans who picked up the obscure French edition of the console and a Dragon Ball game to go with it.

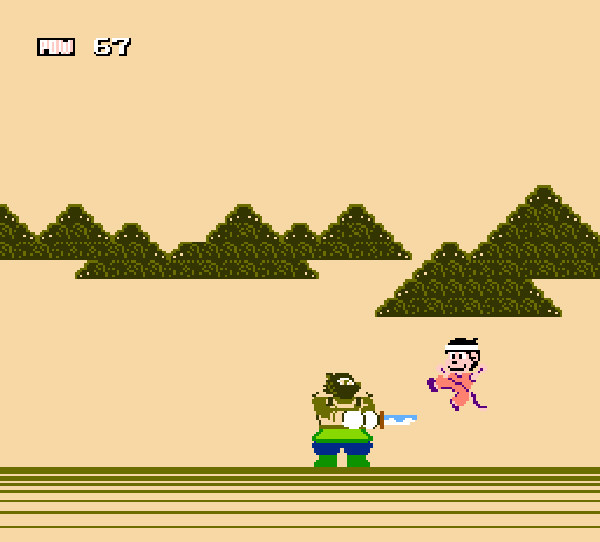

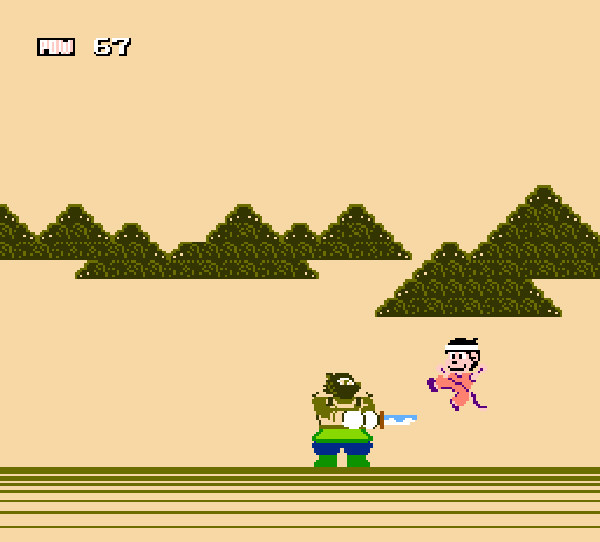

Dragon Daihikyou is primitive, though it at least aims for variety. Goku hops on his cloud and whacks enemies in vertical-scrolling shooter levels, followed by side-view bouts against major Dragon Ball foes. This would be Epoch's only console Dragon Ball title, as the series drifted to Bandai as far as video games went. It's erroneous but amusing to think of Epoch's upper management casually letting Bandai take Dragon Ball, confident that it's just another action manga license with a three-year lifespan at best.

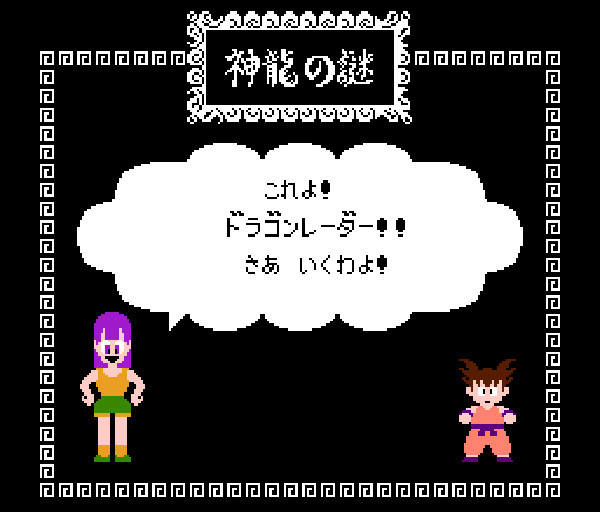

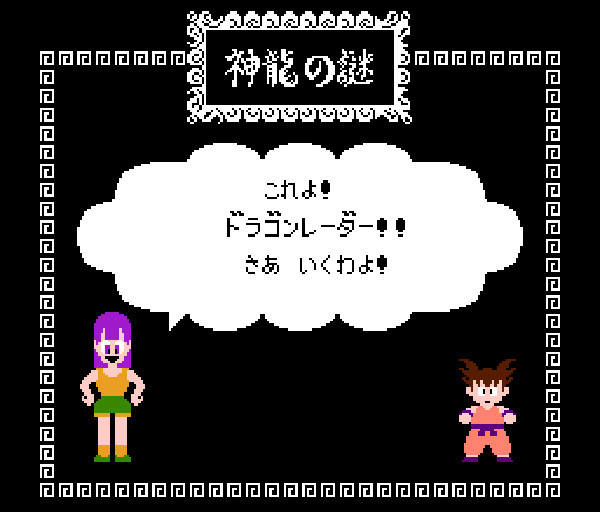

Bandai soon cranked out Dragon Ball titles for LCD handhelds and Nintendo's 8-Bit Famicom home system. By the end of 1986, Bandai had Dragon Ball: Shenron no Nazo on shelves. Covering the early volumes of the manga, the Famicom game presents Goku in overhead-view stages that lead to boss battles not so different from Dragon Daihikyou.

As with many mid-'80s Famicom games, it's the crude work of a developer exploring new concepts. Yet Shenron no Nazo gave fans an acceptable rendition of Goku's battles against everyone from Oolong and Krillin to Emperor Pilaf's robots. It also marked the first Dragon Ball game from TOSE, a large development house that labored anonymously on many anime-based titles for decades. They're so closely tied to the series that it's easier to denote the old Dragon Ball games that TOSE didn't make.

Shenron no Nazo later became the first Dragon Ball game released in North America. Sort of. Bandai was an early supporter of the Nintendo Entertainment System, a heavily redesigned American version of the Famicom, and they built a small catalog by revamping licensed anime by-products. A Famciom game based on Fujiko Fujio's Obake Q-Taro became Chubby Cherub in America, swapping a ghost hero for a big-mouthed angel. The monstrous sights of a Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro title turned into the generic Ninja Kid on the NES.

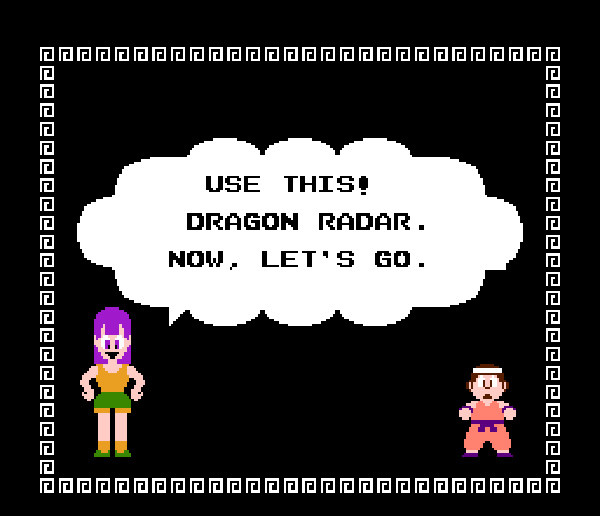

Dragon Ball: Shenron no Nazo got the same makeover when it came to America as Dragon Power in 1988. Goku's spiky hair vanished in favor of a short cut and a more simian appearance, hewing closer to the monkey hero of Journey to the West (a connection played up even in Nintendo Power). Other characters get name changes or complete redesigns: Bulma's simply renamed “Nora,” while Master Roshi's replaced entirely by a long-bearded hermit who now begs for her triangular “sandwich” instead of a peek at her underwear. Feel free to debate whether this is an improvement or not.

In Bandai's defense, Dragon Ball had little cachet in North America. Harmony Gold had a dubbed pilot of the TV series in the pipeline, but it never grew from that. Europe had much more access to Dragon Ball anime, however, and so Shenron No Nazo arrived there without major edits and plainly titled Dragon Ball. In doing so, it told the future: Europe would get more Dragon Ball games in the years to come, but it would be nearly a decade until North America saw anything else localized.

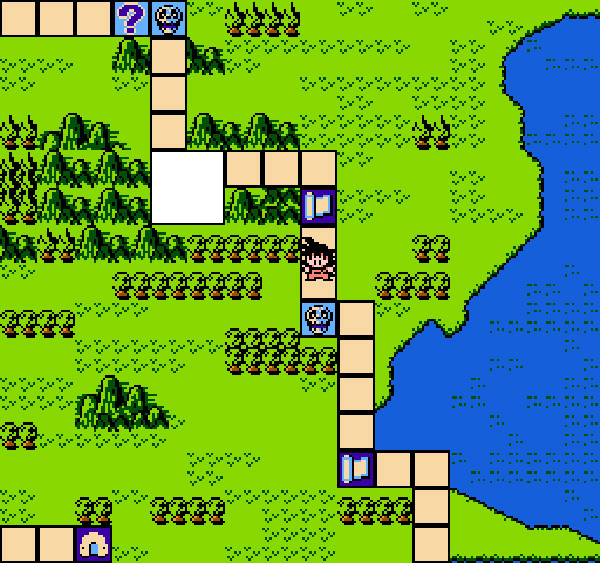

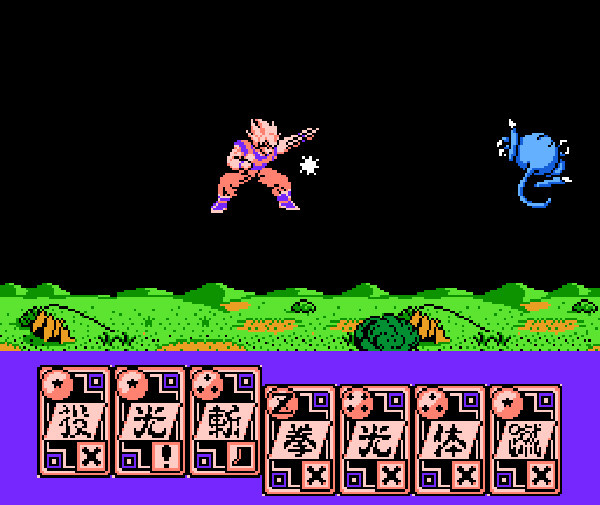

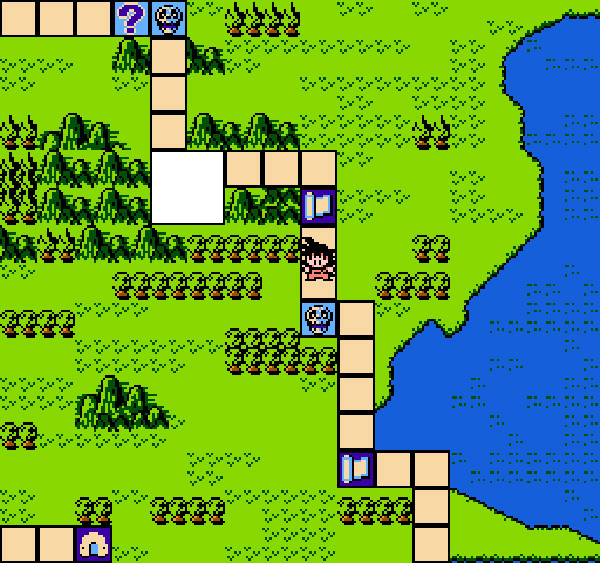

This didn't bother Bandai, too busy churning out Dragon Ball games for Japan. Dragon Ball: Daimao Fukkatsu changed a few traditions when it appeared in 1988. Instead of an action title, it's a role-playing game where Goku navigates areas through menus and fights battles via a cardlike interface. This shift toward RPGs continued the following year, when Dragon Ball 3: Gokuden (above) let Goku roam the world as a board game.

The Famicom also introduced Goku to the lucrative realm of crossovers. Famicom Jump: Hero Retsuden brought together stars from the entire history of Weekly Shonen Jump into a single RPG, letting Goku quest alongside Kenshiro from Fist of the North or meet the cast of Toilet Hakase, just to name two famous examples. Goku also became one of the few characters to return in a starring role for the sequels, 1991's Famicom Jump II and 1993's Game Boy-exclusive Cult Jump.

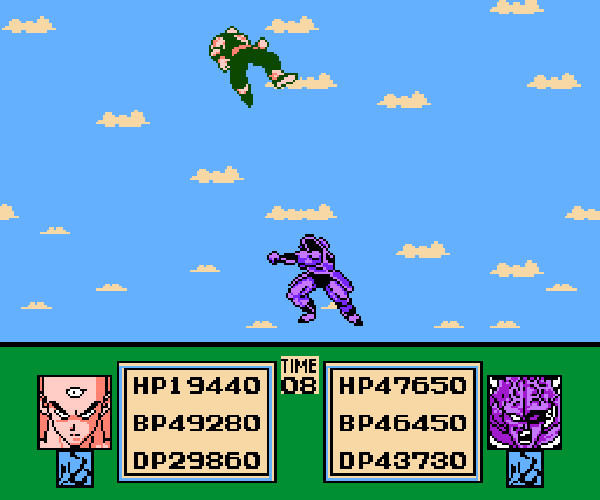

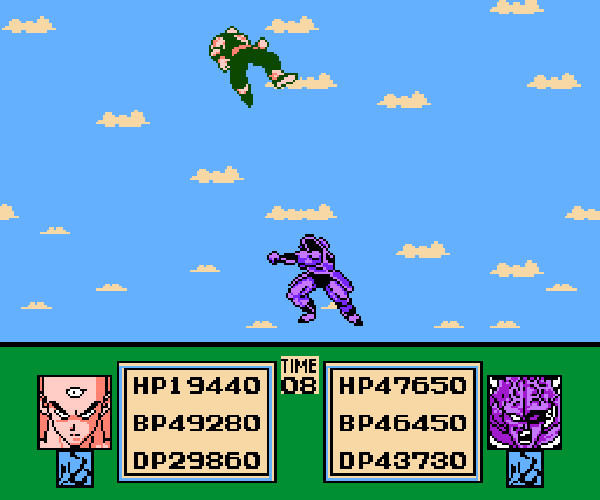

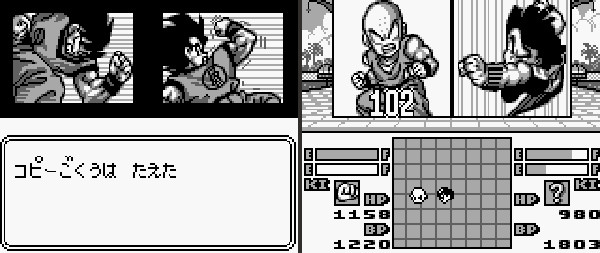

By 1990, Dragon Ball anime had given way to the more violent theatrics and older characters of Dragon Ball Z, and the games caught up. The Gokuden sub-series continued with Dragon Ball Z: Kyoshu! Saiyan, an RPG that follows Goku's new quest up to his battle with ape-ified Vegeta. Combat takes place on black backgrounds, while characters fight stripped-down simulations of Dragon Ball Z brawling.

It may seem strange that Bandai was so eager to turn Dragon Ball and its follow-up into RPGs rather than action-adventure games, but such were the times. Dragon Quest was a role-playing game phenomenon in Japan throughout the late 1980s, with Final Fantasy close behind. Bandai assumed that kids used to popular RPGs would find their elements familiar and untaxing in a Dragon Ball game. Bandai was right.

The concept worked well enough for two more Dragon Ball Z RPGs on the Famicom: 1991's Gekishin Frieza finished the Namek story arc and led into the fight with Frieza, and 1992's Ressen Jinzoningen took things up to the conflict with Cell. None of these Dragon Ball Z RPGs would come to the U.S., but readers of Nintendo Power saw Gekishin Frieza in an imports-only roundup in 1991. For a perfect example of just how little-known the series was among American audiences, note that Nintendo Power referred to it as “Dragon Ballz II.”

Dragon Ball Z games have a habit of appearing on Bandai's odd fringe creations. One such device was the Terebikko, a “video communication system." In effect, it's a four-button toy telephone that hooks into a TV or VCR. Evolved from an older "Dragon Ball TV Telephone" game, it runs in conjunction with certain VHS tapes and lets players (presumably very young ones) answer questions posed by their favorite cartoon characters. American kids would know the Terebikko as the See 'N Say Video Phone, minus any anime games.

Dragon Ball Z: Atsumare! Goku Warudo finds Goku and his companion observing past adventures via time machine, presenting both new footage and recycled scenes. Most of the Terebikko-posed questions cover Dragon Ball lore, missing any opportunities for Goku and Bulma to quiz children about Sub-Saharan geography or the periodic table.

Dragon Ball had grown content with its RPG outings, but the game industry changed tracks in 1992. Street Fighter II hit like a meteor (or, if you insist, an undefended Hadouken) and sent every company scrambling to make their own one-on-one fighting games. Dragon Ball Z's fisticuffs-heavy storylines couldn't ask for a more fitting genre, though Bandai's first attempt piggybacked atop another prevailing trend in Japan: barcode card readers.

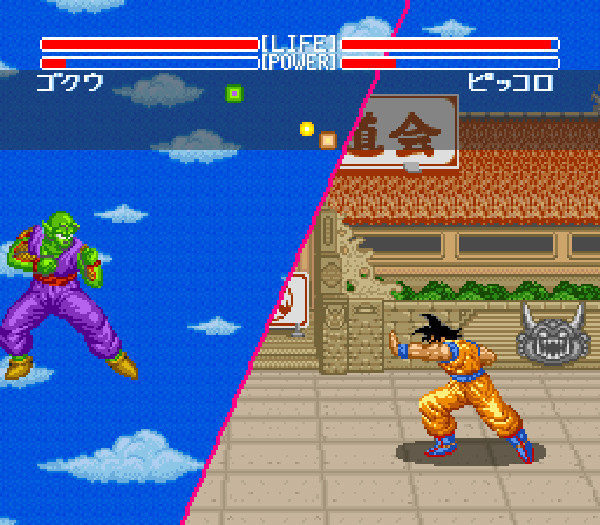

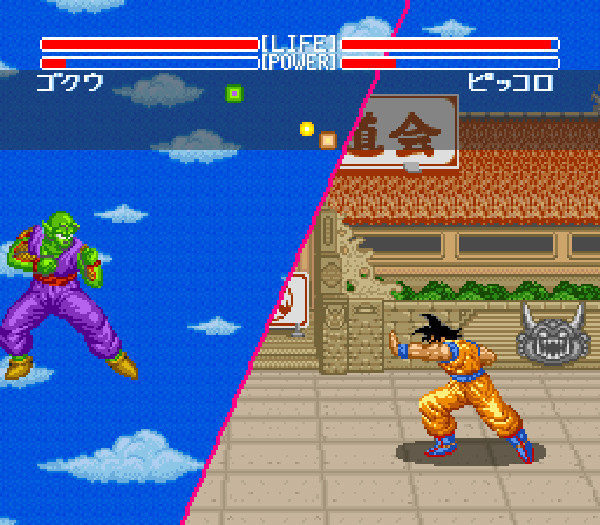

One could easily dismiss Super Butoden as a middling fighter. It offers little over a dozen playable characters, it's assembled with TOSE's usual workmanlike approach, and it confuses players by mimicking long-distance fights with a split screen. Yet it was impressive to Dragon Ball Z fans in 1993 and popular enough to launch its own sub-series. Super Butoden 2 arrived by the end of year, Super Butoden 3 appeared in 1994, and Buyu Retsuden came to Sega's Mega Drive (that'd be the Japanese version of the Genesis). The line even lasted beyond the 16-bit era.

Dragon Ball's shift toward fighting games brought an unintended bonus: more exposure in the West. All three Super Butoden games and Buyu Retsuden saw release in Europe, and while none of them came to North America at the time, they still drew attention. American magazines gave the Super Butoden games ample space in their import coverage, and any enterprising Dragon Ball Z fans found it easy (if expensive) to order the games from vendors. The Super NES and Genesis had region locks swiftly circumvented, and if Dragon Ball's older RPGs demanded Japanese language skills, just about anyone could play a DBZ fighting game.

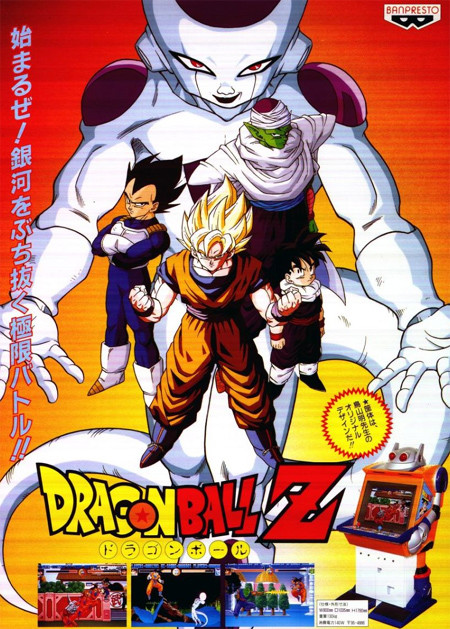

Dragon Ball Z games were a common enough sight in American game rags of the mid-1990s, and it wasn't out of the question to see them in arcades. There's no official record of Banpresto's 1993 arcade fighting game, merely dubbed Dragon Ball Z, showing up in America, but it didn't do poorly in Japan, and some Western arcade owners, scrupulously or not, may well have imported the game. If so, they probably didn't shell out for its robot-Goku cabinet.

Dragon Ball Z: V.R. V.S. was a rarer arcade sight in or out of Japan. It's a 3-D fighting game that depicts battles between Goku and other Dragon Ball regulars (plus an all-new boss named Ozotto) in split-screen, behind-the-back view. Released on Sega's System 32 hardware, V.R. V.S. appeared with both conventional controls and motion-sensing inputs, and the 3DO home console eyed it for a port that never came to be.

Not that fighting games dominated Dragon Ball Z entirely. Bandai gave the Famicom a sendoff in 1993 with Dragon Ball Z Gaiden: Saiyajin Zestumetsu Keikaku, or “The Plan to Eradicate the Saiyans.” Previous Dragon Ball games introduced original characters here and there, but Gaiden brought along an all-new storyline, one in which the vengeful Dr. Lychee mounted a vicious assault on Goku and other members of the Saiyan race.

Reluctant to leave any gaps, Bandai and Toei put out a new Dragon Ball OVA for Dragon Ball Z Gaiden: Saiyajin Zestumetsu Keikaku (above), serving as both a cliff-notes rundown and strategy guide for the game's events. Gaiden never saw an official translation, but Western audiences would get the OVA in due time. Bandai Namco included a remake of it with Dragon Ball: Raging Blast 2 in 2010.

The Playdia had kids in mind with its blue-green casing and lone infrared controller. which docks adorably into the system. It might have been a mediocre console, but it was nice to see a system that didn't leave its gamepad hanging. The Playdia's unfortunate library of games, published almost entirely by Bandai, subsisted on educational software and full-motion-video titles based on popular franchises like Gundam, Ultraman, Sailor Moon, and, of course, Dragon Ball Z.

The two Dragon Ball Z games on the Playdia, Shin Saiyajin Zetsumetsu Keikaku Chikyū-Hen and Shin Saiyajin Zetsumetsu Keikaku Uchū Hen turn the Plan to Eradicate the Saiyans OVA into a marginally interactive game. The player watches footage, picks an option (often choosing where to punch), and then watches even more footage. As with the majority of mid-1990s FMV, there's little sense of gameplay, but Playdia owners couldn't be choosy. In fact, they still can't be choosy. If you're tracking down the system today, you may as well get some Dragon Ball Z game-movies with it.

By 1994, Dragon Ball games could lay claim to just about every major console. The PC Engine, popular Japanese cousin of America's ill-fated TurboGrafx-16, had Dragon Ball Z: Idainaru Son Goku Densetsu, a fighting game that emphasizes cinematic flair. Players have less control over Goku than a typical fighter allows, and cutscenes frequently unfurl in the sprite-based style common to early CD-based games like Ys and Lunar. At the very least, its look aged much better than digitized video clips.

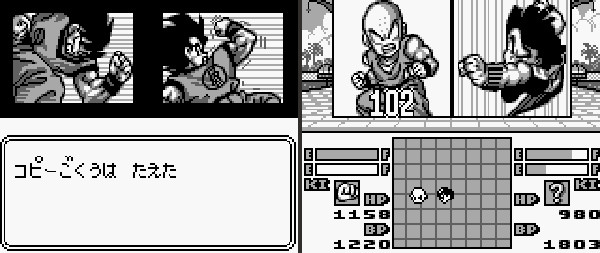

One curiosity of Dragon Ball is how long it took to reach the Game Boy. Nintendo's black-and-white handheld debuted in 1989, but Goku's only appearance there for five years was the crossover Cult Jump. Did Bandai view the Game Boy as a rival to their own cheaper LCD handheld Dragon Ball games? Perhaps.

Just as Bandai's yearly influx of Dragon Ball LCD titles slowed in 1994, the company released Goku Hishoden (left), a Game Boy RPG that covered the earlier arcs of Dragon Ball Z. Goku Gekitoden (right) followed within a year, depicting the Namek storyline and adding more interaction and slightly flashier combat. Even so, they were the portable equivalents of Dragon Ball's Famicom RPGs: fun only for dedicated fans.

The game industry will never again see a year as busy as 1995. Nintendo's Super NES still reigned in Japan and America, Sega's Genesis had a lingering hold in the West, the fighting-game craze dominated arcades, the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn had launched, and beneath all this bubbled a sea of second-string systems stretching from the Atari Jaguar to the NEC PC-FX. Dragon Ball games couldn't visit all of these consoles, but they sure tried.

Banpresto delivered a second arcade fighter with Dragon Ball Z 2: Super Battle, though it was quickly lost in a flurry of other 1995 fighting games and never officially left Japan. This would be the last Dragon Ball arcade game for a good while, unless one counts redemption machines and UFO catchers full of plush Puars.

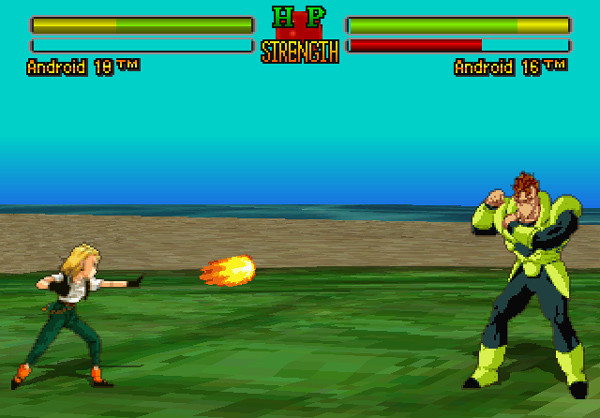

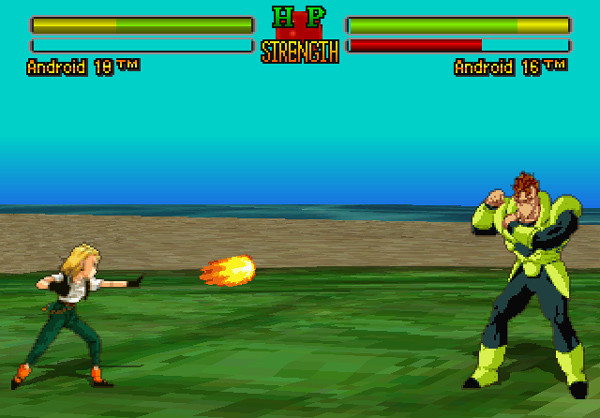

The original Sony PlayStation would soon overtake the Sega Saturn worldwide, but in 1995 the two systems were on equal footing. Each got a Dragon Ball Z fighter in the Butoden vein. The PlayStation was first in line with Ultimate Battle 22, which mixed muddy 2-D sprites of Dragon Ball characters with primitive 3-D backgrounds. The Sega Saturn had to wait a little longer, and its Dragon Ball Z fighter, Shin Butoden offered much the same concept and reused many sprites from Ultimate Battle 22.

If the children of 1995 had no new consoles or old Super Famicoms or even battered Game Boys, they could get a Dragon Ball fix from Bandai's Design Master Senshi Mangajuku, a basic handheld system with a black-and-white touch screen. Two Dragon Ball titles, Manga Kasette and Taisen Kata Game Kasette, let players draw and manipulate characters with the stylus. So don't let anyone tell you that Nintendo invented stylus gameplay with the DS.

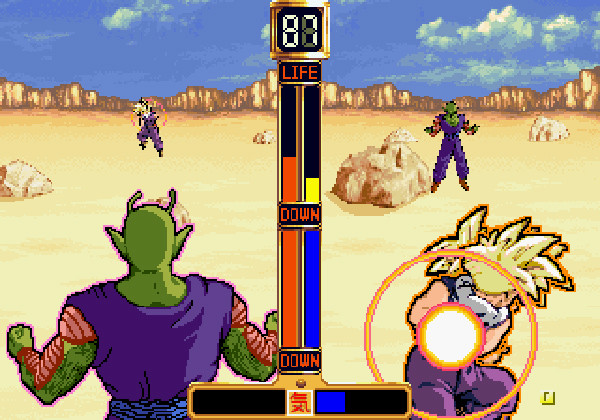

As the game-industry pandemonium of 1995 settled into a more predictable system war in 1996, Dragon Ball games grew scarcer. Dragon Ball Z: Hyper Dimension bid farewell to the 16-bit era with one final Super Famicom fighting game from the TOSE factory. The PlayStation and Saturn also shared another fighter with Dragon Ball Z: Idainaru Dragon Ball Densetsu (above). Wisely shortened to Dragon Ball Z: The Legend for some Western countries, it emphasizes aerial fighting and uses 3-D backgrounds to better effect than Ultimate Battle 22, though at the cost of smaller characters. In Europe, the two consoles divided things: the PlayStation got Ultimate Battle 22, while the Saturn had a localized Dragon Ball Z: The Legend just in time for Christmas 1996--which was, incidentally, the last time the Saturn put up any real fight outside of Japan.

Even with Dragon Ball games on the decline, Bandai found time to work fringe titles into the mix. Anime Designer: Dragon Ball Z for computers and the Bandai-backed Pippin console let fans arrange Saiyans and kaio-ken blasts as they liked.

Dragon Ball reached a crossroads in 1997. Toriyama had wrapped up the original manga two years prior, the Dragon Ball Z anime series had ended in 1996, and the attempted follow-up, Dragon Ball GT, wasn't …well, it wasn't as well-received. But it was still Dragon Ball, and it earned a game: an awful 3-D fighter called Dragon Ball GT Final Bout. The hand-drawn sprites of previous Dragon Ball fighters were gone, replaced by less appealing 3-D graphics that paled before contemporaries like Soul Blade, Tekken 2, and even Lightning Legend.

Dragon Ball GT: Final Bout stood out in one regard, however: Bandai released it in North America. Dragon Ball Z was by then airing on syndicated American TV, and that led Bandai to take a chance. Final Bout saw a very limited release, estimated at 10,000 copies, and it was very easy to miss unless you happened to drop by an Electronics Boutique or Software Etc. on the right day. By decade's end it was an expensive rarity among fans hungry for any Dragon Ball game that didn't require an import adapter or a few semesters of Japanese.

Dragon Ball games waned in Japan. A motion-sensing Dragon Ball tech demo amounted to nothing, and no games from any section of the series were released for the rest of the 1990s. In North America, however, things were different. Over the next few years, Dragon Ball Z went from a syndicated obscurity to a Cartoon Network staple, and kids everywhere started to notice it--and anime in general. Dragon Ball might have slouched in Japan by 1997, but overseas its story was just beginning.

That's all for Part 1 of our history of Dragon Ball games! Stay tuned for the second half, where we'll cover Dragon Ball's rise in America and a few titles that, surprisingly, aren't fighting games!

Source : animenewsnetwork.com

Of course, Dragon Ball is one of those stories seemingly made for video games, whether it's the goofy adventures of a young Goku or the somewhat darker intergalactic brawls of a grown-up Goku, his family, and a limitless cosmos of hostile aliens. The Saiyan hero and his retinue are superheroes with absurd powers and comical overtones, and they fit right into video games from basic shooters to cutting-edge fighters.

But where did it all begin? If you want to be technical about it, the first Dragon Ball video game was a self-contained LCD handheld device entitled Dragon Ball: Pilaf no Gyukushu. Toy-and-game heavyweight Epoch Co. released it in August 1986 with a second game, Taiketsu Son Goku, right on its heels. Like Nintendo's Game and Watch series and other LCD gadgets of the day, these games offer simple black-and-white graphics, and playing one is akin to messing around with a violent calculator. And let's face it: those LCD trinkets don't count as real video games. Just ask any kid who ever got a Tiger Electronics handheld instead of a Game Boy for Christmas.

The first full-fledged Dragon Ball games wouldn't be far behind, though. A month after their LCD handhelds hit the market in 1986, Epoch released Dragon Ball: Dragon Daihikyou for their Super Cassette Vision. The original Cassette Vision and its Super successor were short-lived pioneers of the console market. Dwarfed by Nintendo and Sega systems, they were rarely seen outside Japan. Few were the Europeans who picked up the obscure French edition of the console and a Dragon Ball game to go with it.

Dragon Daihikyou is primitive, though it at least aims for variety. Goku hops on his cloud and whacks enemies in vertical-scrolling shooter levels, followed by side-view bouts against major Dragon Ball foes. This would be Epoch's only console Dragon Ball title, as the series drifted to Bandai as far as video games went. It's erroneous but amusing to think of Epoch's upper management casually letting Bandai take Dragon Ball, confident that it's just another action manga license with a three-year lifespan at best.

Bandai soon cranked out Dragon Ball titles for LCD handhelds and Nintendo's 8-Bit Famicom home system. By the end of 1986, Bandai had Dragon Ball: Shenron no Nazo on shelves. Covering the early volumes of the manga, the Famicom game presents Goku in overhead-view stages that lead to boss battles not so different from Dragon Daihikyou.

As with many mid-'80s Famicom games, it's the crude work of a developer exploring new concepts. Yet Shenron no Nazo gave fans an acceptable rendition of Goku's battles against everyone from Oolong and Krillin to Emperor Pilaf's robots. It also marked the first Dragon Ball game from TOSE, a large development house that labored anonymously on many anime-based titles for decades. They're so closely tied to the series that it's easier to denote the old Dragon Ball games that TOSE didn't make.

Shenron no Nazo later became the first Dragon Ball game released in North America. Sort of. Bandai was an early supporter of the Nintendo Entertainment System, a heavily redesigned American version of the Famicom, and they built a small catalog by revamping licensed anime by-products. A Famciom game based on Fujiko Fujio's Obake Q-Taro became Chubby Cherub in America, swapping a ghost hero for a big-mouthed angel. The monstrous sights of a Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro title turned into the generic Ninja Kid on the NES.

Dragon Ball: Shenron no Nazo got the same makeover when it came to America as Dragon Power in 1988. Goku's spiky hair vanished in favor of a short cut and a more simian appearance, hewing closer to the monkey hero of Journey to the West (a connection played up even in Nintendo Power). Other characters get name changes or complete redesigns: Bulma's simply renamed “Nora,” while Master Roshi's replaced entirely by a long-bearded hermit who now begs for her triangular “sandwich” instead of a peek at her underwear. Feel free to debate whether this is an improvement or not.

In Bandai's defense, Dragon Ball had little cachet in North America. Harmony Gold had a dubbed pilot of the TV series in the pipeline, but it never grew from that. Europe had much more access to Dragon Ball anime, however, and so Shenron No Nazo arrived there without major edits and plainly titled Dragon Ball. In doing so, it told the future: Europe would get more Dragon Ball games in the years to come, but it would be nearly a decade until North America saw anything else localized.

This didn't bother Bandai, too busy churning out Dragon Ball games for Japan. Dragon Ball: Daimao Fukkatsu changed a few traditions when it appeared in 1988. Instead of an action title, it's a role-playing game where Goku navigates areas through menus and fights battles via a cardlike interface. This shift toward RPGs continued the following year, when Dragon Ball 3: Gokuden (above) let Goku roam the world as a board game.

The Famicom also introduced Goku to the lucrative realm of crossovers. Famicom Jump: Hero Retsuden brought together stars from the entire history of Weekly Shonen Jump into a single RPG, letting Goku quest alongside Kenshiro from Fist of the North or meet the cast of Toilet Hakase, just to name two famous examples. Goku also became one of the few characters to return in a starring role for the sequels, 1991's Famicom Jump II and 1993's Game Boy-exclusive Cult Jump.

By 1990, Dragon Ball anime had given way to the more violent theatrics and older characters of Dragon Ball Z, and the games caught up. The Gokuden sub-series continued with Dragon Ball Z: Kyoshu! Saiyan, an RPG that follows Goku's new quest up to his battle with ape-ified Vegeta. Combat takes place on black backgrounds, while characters fight stripped-down simulations of Dragon Ball Z brawling.

It may seem strange that Bandai was so eager to turn Dragon Ball and its follow-up into RPGs rather than action-adventure games, but such were the times. Dragon Quest was a role-playing game phenomenon in Japan throughout the late 1980s, with Final Fantasy close behind. Bandai assumed that kids used to popular RPGs would find their elements familiar and untaxing in a Dragon Ball game. Bandai was right.

The concept worked well enough for two more Dragon Ball Z RPGs on the Famicom: 1991's Gekishin Frieza finished the Namek story arc and led into the fight with Frieza, and 1992's Ressen Jinzoningen took things up to the conflict with Cell. None of these Dragon Ball Z RPGs would come to the U.S., but readers of Nintendo Power saw Gekishin Frieza in an imports-only roundup in 1991. For a perfect example of just how little-known the series was among American audiences, note that Nintendo Power referred to it as “Dragon Ballz II.”

Dragon Ball Z games have a habit of appearing on Bandai's odd fringe creations. One such device was the Terebikko, a “video communication system." In effect, it's a four-button toy telephone that hooks into a TV or VCR. Evolved from an older "Dragon Ball TV Telephone" game, it runs in conjunction with certain VHS tapes and lets players (presumably very young ones) answer questions posed by their favorite cartoon characters. American kids would know the Terebikko as the See 'N Say Video Phone, minus any anime games.

Dragon Ball Z: Atsumare! Goku Warudo finds Goku and his companion observing past adventures via time machine, presenting both new footage and recycled scenes. Most of the Terebikko-posed questions cover Dragon Ball lore, missing any opportunities for Goku and Bulma to quiz children about Sub-Saharan geography or the periodic table.

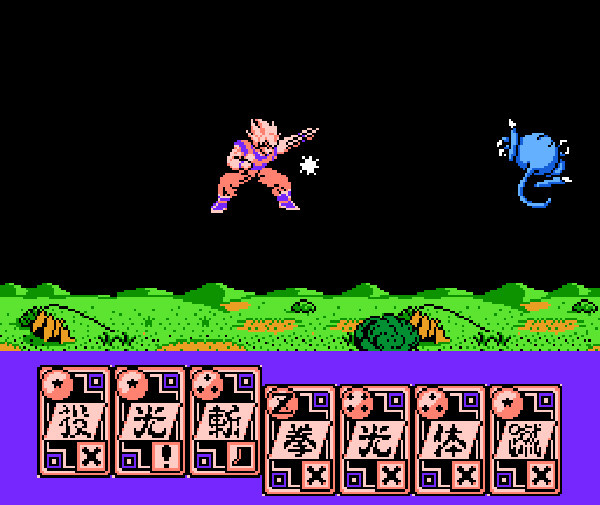

Dragon Ball had grown content with its RPG outings, but the game industry changed tracks in 1992. Street Fighter II hit like a meteor (or, if you insist, an undefended Hadouken) and sent every company scrambling to make their own one-on-one fighting games. Dragon Ball Z's fisticuffs-heavy storylines couldn't ask for a more fitting genre, though Bandai's first attempt piggybacked atop another prevailing trend in Japan: barcode card readers.

Dragon Ball Z: Gekito Tenkaichi Budokai

offers 28 familiar characters in a fighting game, with power-ups and

bonus fighters enabled by a Datach card reader attached to the Famicom.

The barcode craze was familiar ground to Bandai, but Gekito Tenkaichi Budokai was their first attempt at uniting Dragon Ball and fighting games, and it's an alliance that lasts to this day.

Fighting games also pushed Dragon Ball from the saturated, kid-friendly Famicom market to Nintendo's new Super NES/Super Famicom hardware. The first title there was a mere collection of the first two Dragon Ball Z RPGs from the Famicom, but the second was far more important: a fighting game called Dragon Ball Z: Super Butoden.

One could easily dismiss Super Butoden as a middling fighter. It offers little over a dozen playable characters, it's assembled with TOSE's usual workmanlike approach, and it confuses players by mimicking long-distance fights with a split screen. Yet it was impressive to Dragon Ball Z fans in 1993 and popular enough to launch its own sub-series. Super Butoden 2 arrived by the end of year, Super Butoden 3 appeared in 1994, and Buyu Retsuden came to Sega's Mega Drive (that'd be the Japanese version of the Genesis). The line even lasted beyond the 16-bit era.

Dragon Ball's shift toward fighting games brought an unintended bonus: more exposure in the West. All three Super Butoden games and Buyu Retsuden saw release in Europe, and while none of them came to North America at the time, they still drew attention. American magazines gave the Super Butoden games ample space in their import coverage, and any enterprising Dragon Ball Z fans found it easy (if expensive) to order the games from vendors. The Super NES and Genesis had region locks swiftly circumvented, and if Dragon Ball's older RPGs demanded Japanese language skills, just about anyone could play a DBZ fighting game.

Dragon Ball Z games were a common enough sight in American game rags of the mid-1990s, and it wasn't out of the question to see them in arcades. There's no official record of Banpresto's 1993 arcade fighting game, merely dubbed Dragon Ball Z, showing up in America, but it didn't do poorly in Japan, and some Western arcade owners, scrupulously or not, may well have imported the game. If so, they probably didn't shell out for its robot-Goku cabinet.

Dragon Ball Z: V.R. V.S. was a rarer arcade sight in or out of Japan. It's a 3-D fighting game that depicts battles between Goku and other Dragon Ball regulars (plus an all-new boss named Ozotto) in split-screen, behind-the-back view. Released on Sega's System 32 hardware, V.R. V.S. appeared with both conventional controls and motion-sensing inputs, and the 3DO home console eyed it for a port that never came to be.

Not that fighting games dominated Dragon Ball Z entirely. Bandai gave the Famicom a sendoff in 1993 with Dragon Ball Z Gaiden: Saiyajin Zestumetsu Keikaku, or “The Plan to Eradicate the Saiyans.” Previous Dragon Ball games introduced original characters here and there, but Gaiden brought along an all-new storyline, one in which the vengeful Dr. Lychee mounted a vicious assault on Goku and other members of the Saiyan race.

Reluctant to leave any gaps, Bandai and Toei put out a new Dragon Ball OVA for Dragon Ball Z Gaiden: Saiyajin Zestumetsu Keikaku (above), serving as both a cliff-notes rundown and strategy guide for the game's events. Gaiden never saw an official translation, but Western audiences would get the OVA in due time. Bandai Namco included a remake of it with Dragon Ball: Raging Blast 2 in 2010.

The 1990s were an age of multimedia crazes. Game companies stood

convinced that players wanted nothing more than long, grainy video clips

interrupted by the occasional button press. Bandai jumped headfirst

into the fad and created a game system that embodies the

full-motion-video trend better than anything else: the Playdia.

The Playdia had kids in mind with its blue-green casing and lone infrared controller. which docks adorably into the system. It might have been a mediocre console, but it was nice to see a system that didn't leave its gamepad hanging. The Playdia's unfortunate library of games, published almost entirely by Bandai, subsisted on educational software and full-motion-video titles based on popular franchises like Gundam, Ultraman, Sailor Moon, and, of course, Dragon Ball Z.

The two Dragon Ball Z games on the Playdia, Shin Saiyajin Zetsumetsu Keikaku Chikyū-Hen and Shin Saiyajin Zetsumetsu Keikaku Uchū Hen turn the Plan to Eradicate the Saiyans OVA into a marginally interactive game. The player watches footage, picks an option (often choosing where to punch), and then watches even more footage. As with the majority of mid-1990s FMV, there's little sense of gameplay, but Playdia owners couldn't be choosy. In fact, they still can't be choosy. If you're tracking down the system today, you may as well get some Dragon Ball Z game-movies with it.

By 1994, Dragon Ball games could lay claim to just about every major console. The PC Engine, popular Japanese cousin of America's ill-fated TurboGrafx-16, had Dragon Ball Z: Idainaru Son Goku Densetsu, a fighting game that emphasizes cinematic flair. Players have less control over Goku than a typical fighter allows, and cutscenes frequently unfurl in the sprite-based style common to early CD-based games like Ys and Lunar. At the very least, its look aged much better than digitized video clips.

One curiosity of Dragon Ball is how long it took to reach the Game Boy. Nintendo's black-and-white handheld debuted in 1989, but Goku's only appearance there for five years was the crossover Cult Jump. Did Bandai view the Game Boy as a rival to their own cheaper LCD handheld Dragon Ball games? Perhaps.

Just as Bandai's yearly influx of Dragon Ball LCD titles slowed in 1994, the company released Goku Hishoden (left), a Game Boy RPG that covered the earlier arcs of Dragon Ball Z. Goku Gekitoden (right) followed within a year, depicting the Namek storyline and adding more interaction and slightly flashier combat. Even so, they were the portable equivalents of Dragon Ball's Famicom RPGs: fun only for dedicated fans.

The game industry will never again see a year as busy as 1995. Nintendo's Super NES still reigned in Japan and America, Sega's Genesis had a lingering hold in the West, the fighting-game craze dominated arcades, the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn had launched, and beneath all this bubbled a sea of second-string systems stretching from the Atari Jaguar to the NEC PC-FX. Dragon Ball games couldn't visit all of these consoles, but they sure tried.

Banpresto delivered a second arcade fighter with Dragon Ball Z 2: Super Battle, though it was quickly lost in a flurry of other 1995 fighting games and never officially left Japan. This would be the last Dragon Ball arcade game for a good while, unless one counts redemption machines and UFO catchers full of plush Puars.

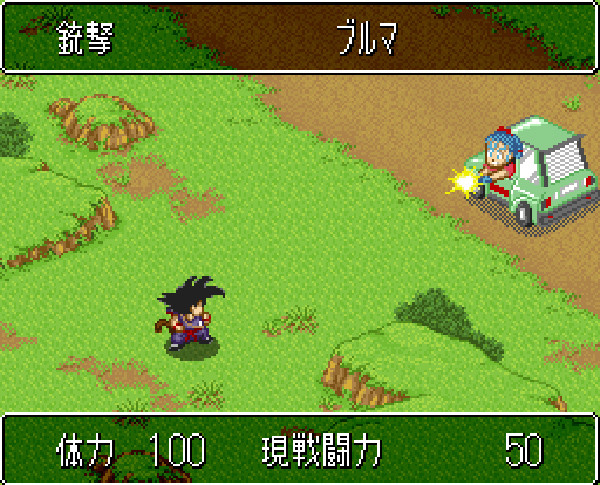

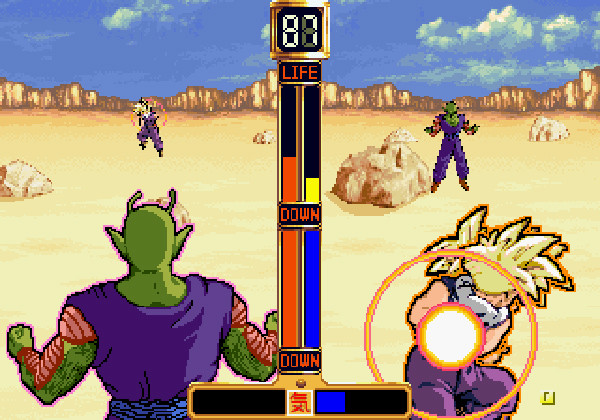

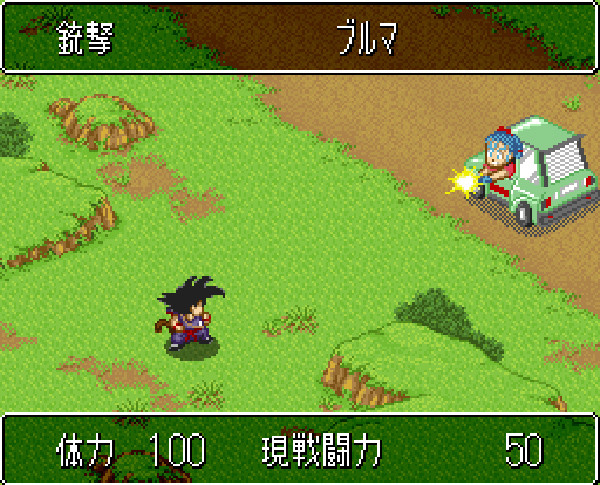

Perhaps sensing the last hurrah of the Super Famicom, Bandai and TOSE managed to release two Dragon Ball Z RPGs there in 1995, continuing the dormant Gokuden series. The first, Super Gokuden: Totsugeki-Hen (above) explores Goku's formative years with RPG maps and diagonally viewed battle scenes. Super Gokuden: Kakusei-Hen uses the same game engine to recreate Dragon Ball Z combat. Neither Super Gokuden

left Japan, but that was the rule for just about every mid-1990s Super

Famicom RPG. In any case, Western fans of the genre were much more

concerned with pipe-dream localizations for Dragon Quest VI, Star Ocean, and any given Squaresoft creation.

The original Sony PlayStation would soon overtake the Sega Saturn worldwide, but in 1995 the two systems were on equal footing. Each got a Dragon Ball Z fighter in the Butoden vein. The PlayStation was first in line with Ultimate Battle 22, which mixed muddy 2-D sprites of Dragon Ball characters with primitive 3-D backgrounds. The Sega Saturn had to wait a little longer, and its Dragon Ball Z fighter, Shin Butoden offered much the same concept and reused many sprites from Ultimate Battle 22.

If the children of 1995 had no new consoles or old Super Famicoms or even battered Game Boys, they could get a Dragon Ball fix from Bandai's Design Master Senshi Mangajuku, a basic handheld system with a black-and-white touch screen. Two Dragon Ball titles, Manga Kasette and Taisen Kata Game Kasette, let players draw and manipulate characters with the stylus. So don't let anyone tell you that Nintendo invented stylus gameplay with the DS.

As the game-industry pandemonium of 1995 settled into a more predictable system war in 1996, Dragon Ball games grew scarcer. Dragon Ball Z: Hyper Dimension bid farewell to the 16-bit era with one final Super Famicom fighting game from the TOSE factory. The PlayStation and Saturn also shared another fighter with Dragon Ball Z: Idainaru Dragon Ball Densetsu (above). Wisely shortened to Dragon Ball Z: The Legend for some Western countries, it emphasizes aerial fighting and uses 3-D backgrounds to better effect than Ultimate Battle 22, though at the cost of smaller characters. In Europe, the two consoles divided things: the PlayStation got Ultimate Battle 22, while the Saturn had a localized Dragon Ball Z: The Legend just in time for Christmas 1996--which was, incidentally, the last time the Saturn put up any real fight outside of Japan.

Even with Dragon Ball games on the decline, Bandai found time to work fringe titles into the mix. Anime Designer: Dragon Ball Z for computers and the Bandai-backed Pippin console let fans arrange Saiyans and kaio-ken blasts as they liked.

Dragon Ball reached a crossroads in 1997. Toriyama had wrapped up the original manga two years prior, the Dragon Ball Z anime series had ended in 1996, and the attempted follow-up, Dragon Ball GT, wasn't …well, it wasn't as well-received. But it was still Dragon Ball, and it earned a game: an awful 3-D fighter called Dragon Ball GT Final Bout. The hand-drawn sprites of previous Dragon Ball fighters were gone, replaced by less appealing 3-D graphics that paled before contemporaries like Soul Blade, Tekken 2, and even Lightning Legend.

Dragon Ball GT: Final Bout stood out in one regard, however: Bandai released it in North America. Dragon Ball Z was by then airing on syndicated American TV, and that led Bandai to take a chance. Final Bout saw a very limited release, estimated at 10,000 copies, and it was very easy to miss unless you happened to drop by an Electronics Boutique or Software Etc. on the right day. By decade's end it was an expensive rarity among fans hungry for any Dragon Ball game that didn't require an import adapter or a few semesters of Japanese.

Dragon Ball games waned in Japan. A motion-sensing Dragon Ball tech demo amounted to nothing, and no games from any section of the series were released for the rest of the 1990s. In North America, however, things were different. Over the next few years, Dragon Ball Z went from a syndicated obscurity to a Cartoon Network staple, and kids everywhere started to notice it--and anime in general. Dragon Ball might have slouched in Japan by 1997, but overseas its story was just beginning.

That's all for Part 1 of our history of Dragon Ball games! Stay tuned for the second half, where we'll cover Dragon Ball's rise in America and a few titles that, surprisingly, aren't fighting games!

Source : animenewsnetwork.com

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps